The Fundamental Steps of Brewing with DR BLUES

Posted in Blog

The process of brewing beer is like a foreign language to many, but if craft beers fans want to truly appreciate the delicious drink in front of them, a basic understanding of the fundamental steps of brewing can be beneficial when imbibing delectable craft brews.

Malt

Brewing begins with raw barley, wheat, oats or rye that has germinated in a malt house. The grain is then dried in a kiln and sometimes roasted, a process that usually takes place in a separate location from the brewery. At the brewery, the malt is sent through a grist mill, cracking open the husks of the kernels, which helps expose the starches during the mashing process. The process of steep milling, or soaking the grain before milling, is also an option for large-scale brewers.

The combination of different types of grain used by a brewer to make a beer is often called the grist bill.

Mashing

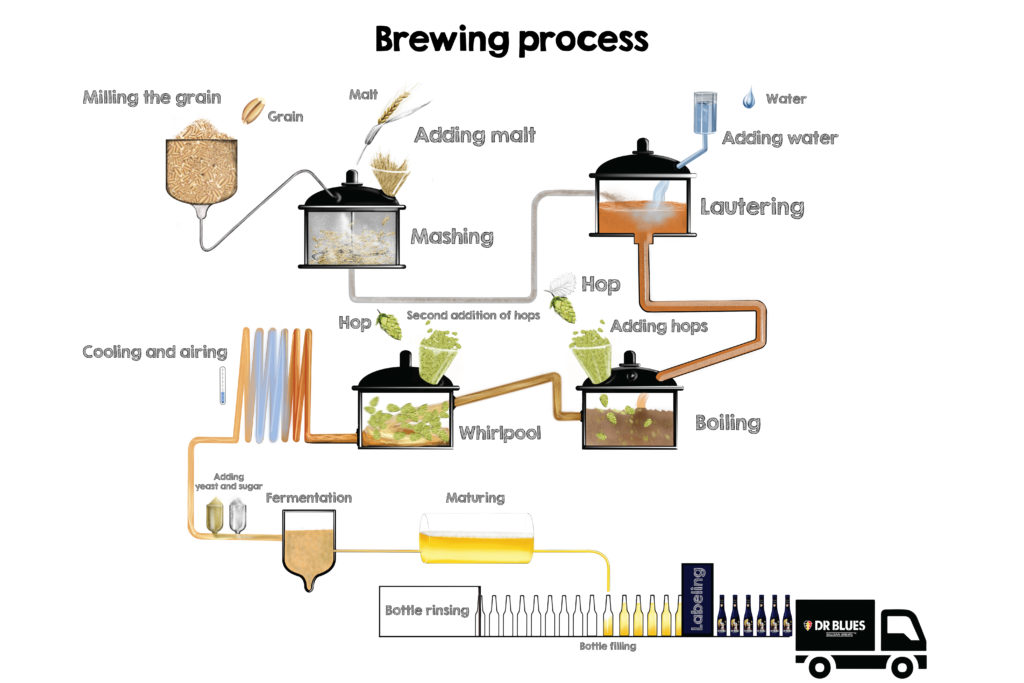

The first step in the beer-making process is mashing, in which the grist, or milled malt, is transferred to the mash tun. Mashing is the process of combining the grist and water, also known as liquor, and heating it to temperatures usually between 100 degrees Fahrenheit up to 170 degrees Fahrenheit. Mashing causes the natural enzymes in the malt to break down starches, converting them to sugars, which will eventually become alcohol. This process takes place in one to two hours. Mash temperatures can be gradually increased or allowed to rest at certain temperatures, choices which are very much part of the brewer’s art. Different temperature levels activate different enzymes and affect the release of proteins and fermentable sugars. Proteins play a smaller role but are important to the creation of foam in a finished beer. For heating, most brewers use steam.

Infusion vs. Decoction Mashing

Water is combined with the grist in one of two ways, infusion or decoction.

In infusion mashing, the grains are heated up in one vessel (the mash tun); in decoction mashing, a portion of the mash is transferred from the mash tun and boiled in a separate vessel (called the mash kettle), then returned to the original mash. Some brewers repeat this process to achieve double decoction and a few are known to use triple decoction.

The liquid consisting of sugars and water resulting from mashing is wort.

Lautering

Lautering is the process of separating the wort from spent grain as efficiently as possible. Generally, it is done in a separate lauter tun, although the process of mash filtering can now be done by large-scale or small-scale brewers.

A lauter tun has a perforated or slotted bottom with runoff ports. The solids from the mash settle on the bottom and form a filter for the wort.

Lautering consists of three steps: mashout, recirculation and sparging. The mashout consists of raising the mash temperature to 170 degrees Fahrenheit, which stops enzymatic reactions and preserves the fermentable sugar profile of the wort, and also makes the wort less viscous and easier to work with.

Next, the wort is drawn out from the bottom of the lauter ton and recirculated, causing loose grain particulates to be filtered out naturally by the grain bed, allowing for more wort clarity.

Once the wort is transferred, the remaining spent grain, which consists of grain husks and particles left over from the mashing, requires sparging. Sparging is the process of rinsing the spent grain with heated water to get as much of the sugars as possible from the remaining grain for the wort.

After sparging, the spent grain is commonly recycled as feed for cattle and hogs, or can be used to make bread.

Boiling

Once a brewer has wort, it is sterilized through a boiling process in a kettle, which halts enzyme activity and condenses the liquid. During the boil, which typically lasts from 60 to 120 minutes, hops are added.

Hopping

The qualities of aroma, taste and bitterness that hops impart to beer depend on what point they are added. Hops can be added early in the boil for bittering, with more time boiled resulting in more bitterness. They can be added mid-boil for flavor, or late boil for flavoring and aroma.

Hops can also be added at stages after the boil during whirl-pooling (flavour/aroma), fermentation (dry-hopping for aroma) or maturation (dry-hopping for aroma).

Whirlpooling

Once the boil is complete, the whirlpool phase further clarifies the wort by removing protein and hop solids through settling. These solids are known as trub. Although the boiling kettle can also be used as a whirlpool, many brewers use a separate, specially designed container.

A hop back is a type of vessel for whirlpooling that employs fresh hop flowers or cones in a sealed chamber for filtering the trub, which adds more hop aroma compounds to the wort. A hop back is often employed when whole hop cones are used in the boil. A standard whirlpool is better at collecting trub created from hop pellets.

Next, a heat exchanger is used to reduce the wort to the temperature desired for fermentation. Water heated by this exchange is often used by brewers to start a new brewing cycle.

Fermentation

Wort is transferred to a fermentation tank and the yeast is pitched, or added. Ale yeast rises to the top of the wort and lager yeast generally collects in the bottom. This stage is the primary fermentation — the conversion of sugars to alcohol and carbon dioxide that lead to an ale or a lager, depending on the type of yeast used. (Hybrid beers also use one of these two types of yeast.)

Once yeast has been pitched at proper temperature, the beer is generally maintained from 60 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit for ales, and 50 degrees Fahrenheit for lagers. The process of the yeast converting sugars to alcohol generates heat and is monitored closely by brewers. The higher temperatures employed for ale yeast result in more esters, or fragrant organic compounds.

Conditioning

During the conditioning process for ales and lagers, the beer will mature and smooth, and by-products of fermentation will diminish. It is possible to dry hop during this stage for added aroma, and other methods such as barrel aging can further introduce complexity.

The cold storage of beer for 30 days known as lagering is a key difference in the cleaner nature and more defined flavors of lagers when compared to ale.

A type of secondary fermentation for lagers is known by the German word kräusening. Once the fermented “green” beer is transferred to tanks for cold storage, kräusening is the introduction of actively fermenting beer, including yeast, to the dormant new beer. The additional yeast helps carbonation and the elimination of unwanted aspects of the primary fermentation such as diacetyl – or butterscotch flavors – and other compounds.

The conditioning process can last from one to six weeks and sometimes more. Depending on the style, brewers may choose to filter any remaining yeast or other particles from the beer and then store it in bright tanks. Some pasteurize their beer to improve clarity and shelf life.

Packaging and Carbonation

Once the beer has fermented, it must be kegged or bottled and carbonated, either naturally or by force. Force carbonation involves adding CO2 to a container under high pressure, forcing it to be absorbed into the beer. Most breweries use force carbonation because it’s a much faster process and allows for greater clarity in the beer.

Krausening is a method to introduce carbonation during the fermenting stage. Bottle conditioning – or adding a small amount of sugar and yeast at bottling – is also used to generate carbonation. Cask-conditioned real ale is carbonated by adding sugar, yeast and hops when the beer is first introduced to the cask.

Experimentation

Experimentation is the soul of the brewing process. Any facet of brewing from ingredients to temperatures to timing can be altered.

Measurements

Key measurements determined by a hydrometer help brewers follow the process of fermentation.

Gravity: Ratio of water to other substances in the water such as sugar.

Original Gravity (OG) – The gravity reading of the wort taken before yeast is pitched.

Final Gravity (FG) — The gravity reading taken after fermentation is complete.

ABV –The Original Gravity and Final Gravity are the key variables in the calculation to determine Alcohol by Volume.

Text source: https://beerconnoisseur.com